Miroslava Urbanová on Riders Exhibition

As we reflect on the mythological images, we are studying the facts of the psyche and trying to interpret them. …

As we consider the basic images of Greek mythology, we should ask what the particular images could mean in our own individual lives.Edward F. Edinger, The Eternal Drama. The Inner Meaning of Greek Mythology

The group exhibition Riders presents works of four female artists with distinctive authorial programme and recognizable painterly technique – of Alena Adamíková, Mária Čorejová, Kristína Mésároš and Oľga Paštéková. In their oeuvres they never abandoned the figurative representation. They are interested in figures, spaces, phenomena and things that could be described as mythological and archetypal. One can read through them the universal human experience, which has been translated into symbolic representations.

Classical mythology is a source of such archetypes, templates and symbolic bearers of certain character traits, aspirations and destinies – of Gods, heroes, Goddesses and heroines. Some of them became a starting point for the latest paintings of Alena Adamíková, who is known for her imaginative portraits. However, she is not interested in the transcription of epic narrative of the protagonists from antiquity in the canonical moment from art history. She focuses on the character traits and psychological potential of chosen figures. She searches in her immediate surroundings for such faces that would express these abstract attributes and qualities, in the eyes and gestures of her family and friends. She tries to free them from two-dimensionality and false realism of portrait, making the pulsating inner life of characters visible by shimmering the range of colours on their skin.

Mária Čorejová works primarily in the media of ink drawing on paper. In her last extensive series, she combined detailed views into naves of European Gothic cathedrals with enigmatic objects floating in the amorphous fluid of ink. She continuously searches for other mysterious and strange places and undefined spaces behind the known territories. We won’t find these places on the map, but still, they are present in the phantasy of different nations and cultures. They are mental pictures that consist of longing projections of human psyché, a Rorschach stain of the searching and the lost. The well-known objects are growing off the possibilities of their material, overflowing into unpredictable contexts, so that their fixed meanings disappear.

The personal mythology of Oľga Paštéková uses the symbolic of wolves, ravens or destroyed woods not only as a metaphor of problematic hierarchies between humans and nature. These seemingly dark creatures and phenomena are taking new contours in her latest works, in which they are situated in the debris of amusement parks. They broke free from mystifying legends thematizing their demonic nature and they represent the return of nature to the former spaces of consumerist simulacrum of amusement for the amusement itself. They are given a voice, gradually insistent, that the artist associates with the Socratic daimonion – an inner voice helping by searching for the good. One only needs to follow it.

The sky in the paintings of Kristína Mésároš is rarely calm and blue – it usually shines with all colours of the rainbow spectrum. This expressive usage of colour makes the atmosphere of strangely quiet, outside-of-time or timeless depictions complete. It emphasizes the inexhaustible archetypal potential of the medium of painting as such. High seats, boats, woods or a road are elements that remain a part of our collective unconsciousness and associate us much more than the object represented. A moonland is not only a dry plain, but an echo of possible scenarios that preceded its formation. This sound of the well-known is amplified with names of the pictures that were in many cases inspired by movies. The outcome is always surprising – without the claim to the only one exclusive interpretation of the story.

Riders is an exhibition of four tireless artists, who find the inspiration for their works in the culturally anchored images and patterns. Subsequently, they update them in the moments of reevaluation, reinterpretation or by making them uncertain. Riders embody emancipatory power, the holding of the reins of one’s own life and image-making and of choosing the individual path within the group.

Miroslava Urbanová, curator

Mária Čorejová: Poviedky

Mária Čorejová (1975, Bratislava) je výtvarníčka, grafická dizajnérka a pedagogička (ŠUP Jozefa Vydru v Bratislave). Hoci svoje koncepty príležitostne realizovala aj v médiách maľby, objektu a videa, jej ťažiskovým výstupom je už niekoľko rokov predovšetkým kresba. Redukovaná čiernobiela farebnosť, špecifická ikonografia, založená na spájaní nesúrodých prvkov do jedného obrazového celku patria k základným charakteristikám Čorejovej tvorby. Jej obrazy sú naplnené silnou, kultúrne podmienenou symbolikou. Medzi časté motívy patria napríklad: kríž, dom, kostol, strom, balón, vzducholoď, atlét a pod. Kombináciou týchto motívov vytvára nové neočakávané spojenia, smerujúce k spochybňovaniu konvenčných významov a zdanlivo bezproblémového chápania vecí alebo kriticky poukazujúce na niektoré súčasné spoločenské a kultúrne fenomény. Základom jej prác (väčšinou ide o kresby tušom na papieri) je akási „tekutá čierna hmota“, ktorá sa prelieva cez plochu obrazu, vytvára a zároveň „požiera“ alebo odkrýva fragmenty priestorov, postáv a objektov.

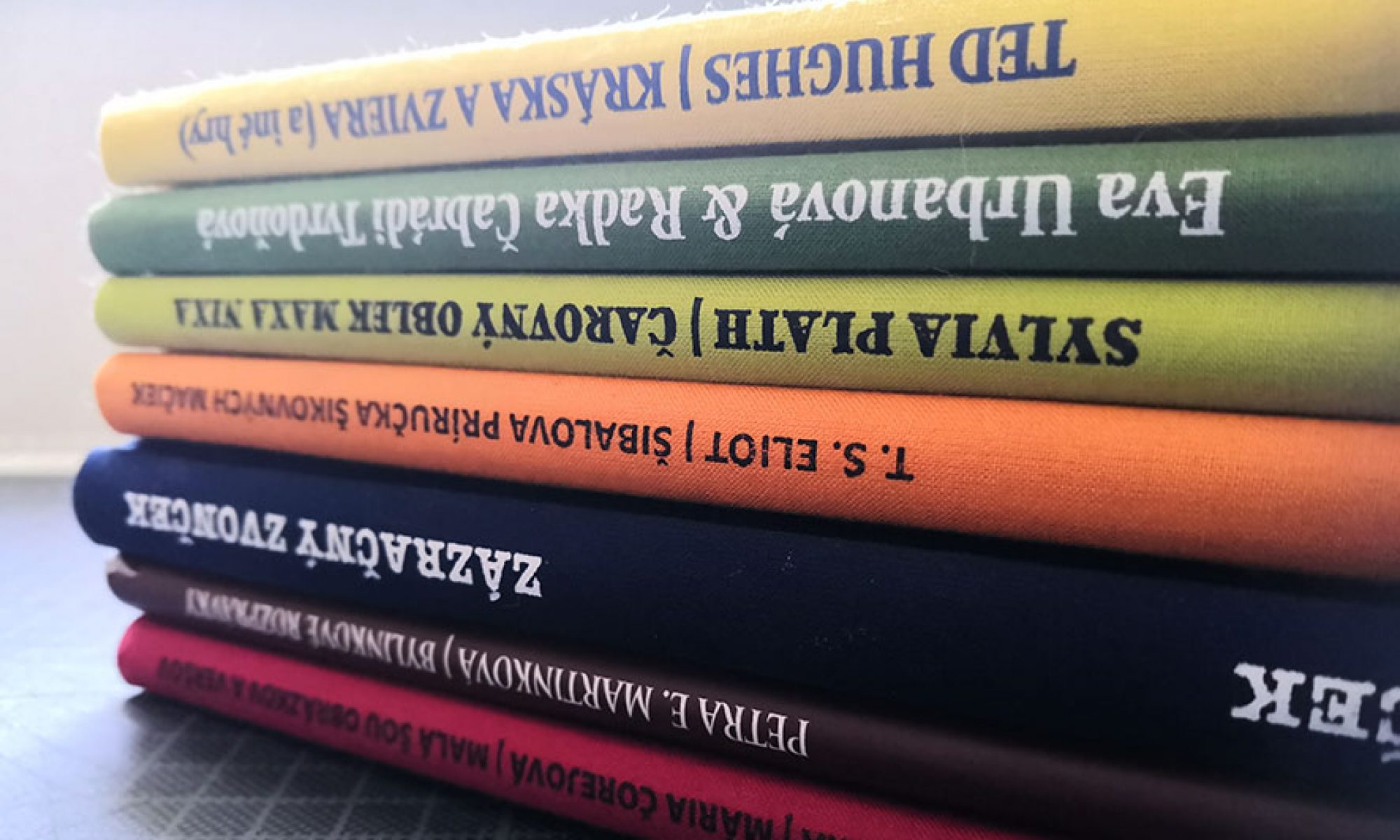

Aktuálna výstava Poviedky v galérii NOVA predstavuje „graficko-dizajnérsku“ polohu tvorby Má-rie Čorejovej. Ide o súbor digitálnych kresieb – knižných ilustrácií, ktoré doteraz neboli výstavne prezentované. Hoci tradičný tuš a papier tu autorka vymieňa za digitálne pero a elektronickú podložku, kresbám nechýba svojbytnosť a autentický „čorejovský“ rukopis. Väčšinu vystavených prác vytvorila k titulom vydaným prešovským vydavateľstvom Fórum alternatívnej kultúry a vzdelávania, s ktorým už niekoľko rokov spolupracuje. Táto spolupráca v Čorejovej prípade zahŕňa nielen ilustrácie, ale aj typografickú úpravu a celú fyzickú podobu zväzku – má teda charakter samostatného tvorivého výstupu. Prezentované práce prezrádzajú jej tesný vzťah k vybraným literárnym textom – predovšetkým k poézií, rôznym poetickým jazykovým útvarom a iným, dnes skôr menšinovým žánrom.

Čorejovej chápanie ilustrácie je založené na skratke, symbole a navodení určitého pocitu. Diváka vyzýva k dialógu a dáva mu priestor na vlastnú predstavivosť. V tomto zmysle Poviedky tematizujú úlohu ilustrátora ako rozprávača, ktorý s čitateľom/vnímateľom komunikuje na inej úrovni než spisovateľ a inými prostriedkami sa snaží sprostredkovať určitý motív, fenomén či emóciu. Ide tu v zásade o grafické znaky, ktoré sú vždy znovu nabité novou energiou a asociatívnou silou. Ich výstavná prezentácia – pripomínajúca knižný layout aplikovaný na steny galérie – pretvára konvenčnú formu výstavy na svojbytný komorný „gesamkunstwerk“.

Naďa Kančevová, kurátorka výstavy

…o výstave Poviedky

Vstúpte do papiera. Aj takto by sa dala vnímať výstava Márie Čorejovej v galérii NOVA, ktorá prebieha od 3. februára do 8. marca 2020. V súvislosti s jej názvom Poviedky možno o výstave uvažovať v dvoch plánoch: jednak ako o zbierke kresieb/ilustrácií vytvorených pre publikácie prešovského vydavateľstva Fórum alternatívnej kultúry a vzdelávania (FACE) a zároveň ako o priestore podnecujúcom ľudskú imagináciu prostredníctvom média. V Čorejovej prípade sa médium slova zamieňa s digitálnou kresbou, aby sme si príbeh sami domysleli. Predstavuje nám však fiktívny svet vo svojej fyzickosti, s jeho postavami, predmetmi i zápletkami, odohrávajúcimi sa na mikroúrovni každého obrazu i na makroúrovni výstavy ako celku.

Hlavnou hýbateľkou tohto sveta je čierna tekutina, či dokonca miazga, ktorej postupným tokom sa napĺňa vnútro predmetov. Či už ide o priestory pôvodne vystavané ľuďmi alebo o hory, ich samotu sprevádza iba táto čierna miazga, ktorá sa ich zmocňuje. Čiernota zasiahla a prestúpila aj človeka, vykorenený strom, či vzducholoď. Niet kam uniknúť, nikto tam nie je.

Existenciálny pocit úzkosti z ekologickej katastrofy, smútok nad odľudštením, žiadna ponuka alternatívy. Za čiernu miazgu si môžete dosadiť čo len chcete, čo vás trápi. Výsledok je rovnaký, zaleje nás to.

Čierna tekutina je pre Čorejovú veľavravným výberom: vo svojich iných kresbách zvykne používať tuš. Tekutina tvorby sa metaforicky stala tekutinou bezvýchodiskovou. To, čo sme si vytvorili, nadobudlo vlastný život a nás už nepotrebuje. Aké príznačné, čo poviete? Príďte si tieto apokalyptické Poviedky prečítať sami.

Zuzana Husárová

poet & theoretician

Standing Waters

The solo show of Mária Čorejová Standing Waters at Bratislava City Gallery presents a selection from her latest drawing series Days of Anger (2015 – 2016), Brave World (2016 – 2017), Standing Waters (2017) and Drawing Restraints (2017), together with the objects by architect Miriam Šebianová Sweet Home (2017). Mária continues to develop her authentic authorial programme prevalently in the technique ink on paper. On the white surface of the paper sheet the objects are assembled in such constellations of which one exclusive interpretation would put us in danger of getting stuck in the shallows.

Days of Anger, referring with its title to the classic of Slovak literature, consist of representations of both everyday objects and universal symbols of our cultural circle, for example bread or boat. Things which are burnt, burning, flowing, or are drowning in themselves, produce the instant feeling of worry about the change of their state and/or state of matter. Mária adapts her technique – this time very soft pencil drawing and scratched black wax – so that she reaches more dramatic contrast, feeling of loss of security after being hit by imaginary lightning of anger.

The newest Drawing Restraints, to which Miriam responds with Sweet Home, are at first sight thematically alike to Days of Anger. On the other hand, as the title suggests, Mária reflects on the possibilities and limits of the drawing media. She does not take into account only its preconditions as space demarcation – paper edges, or its fundamental flatness. At the same time she doubts if there is actually really something except nothing behind the picture. Metal construction of Miriam’s objects shaped as houses delineates in the third dimension a certain physical and ideological space, in the similar way like Mária’s drawing line. Borders of this space are interrupted with motifs from Mária’s usual repertoire, for example balloon or animals, which are searching for their place in the framework of unclear borders between private and public space. Artists are inviting us to take a look at their relationship, its sweet ups and downs, its fragility similar to the sugar walls of one of the little houses.

Christian symbolism and church as religious archetype is emerging in Mária’s oeuvre regularly, last time in the series Stations of Crisis. In the newer Brave World the artist directs our gaze into the interior of sacral architecture: to the naves, transepts and chapels of the cloisters and cathedrals from Middle Ages. These are without doubt the most monumental material and artistic manifestations of the Christian tradition in Europe. She brings various strange objects and phenomena to these spaces and therefore disturbs the genre impression of the drawings. Indeed, these depictions of church interiors denote more metaphysical than physical space, but deprived of its divine aura represented by the light coming through the colourful glass windows. In these mute skeletons are the fragments of the secular world trapped in the iconic black matter/fluid. The artist shifts the discussion to the framework of thinking about systems (religious, social, cultural), about their borders, confrontations and overlaps. According to legends, at the beginning of the world there was light. And at the beginning of the art/painting there was a line drawn alongside the shadow.

The series Standing Waters (California Dreaming) is an outcome of Mária’s this-year microresidency in California, US. Right on spot, in plein-air of the West Coast of America, Mária recorded lonely moments of the group of artists by the means of extremely reduced drawing. It is in no way depiction of impression, neither of shades of feelings. She literally inscribed the static character of the certain moment almost out of time, making visible another here and now beyond the hurry of everyday life.

Miroslava Urbanová

curator

Drawing is probably the oldest way how to note down and share information. It goes together (or can go together) with the formation and organization of ideas and thus enables mental automatism, visualization of subconscious connections and of irrational images. In its system of signs, visual symbols, and their universal speech, everything – even something that is clear or we can say “black on white”– can be interpreted in many ways. Contents may be as intimate, unclear or subjective as it is possible but the notable passion and (in the figurative sense) constant presence of the creator in the form of readable trace of his/her artwork enables us retroactively at least partially reconstruct the procedures he/she used in the creative process. In the case of Mária Čorejová, it is impossible to talk about intuitive or gestic drawing. On the contrary, her artworks act as semantically structured and thought-through visual compositions that originate without any coincidence or spontaneity. She makes use of other essential quality of drawings – of communicativeness.

Within the framework of the today’s fine art, the artwork of this author belongs to that type of art which prefers content over (pompous) form while using graphic and drawing. Her artwork is based on the ink drawing on paper but she does not avoid its interconnection with other types of art such as graphic, product design or computer animation.

However, she is leaving the borders of her favourite technique only rarely. If she does so, she is inviting other artists for cooperation on inter-media manipulation, transmission or on putting finishing touches to her drawings. Among these artists, we can mention for example Sylvia Jokelová, Martin Bu or Matěj Smetana. She almost never works with colours – black ink and white paper are enough to express her thoughts. There is a reason for such an artistic asceticism – in the graphic work of Mária Čorejová, the content is the most important. Her drawing is an independent discipline which suits the best for the main artistic intention – to interpret an idea through a free work with pictorial material. A picture created by her is almost a literary work. She connects and bends messages; she asks questions, she uses metaphors. Through a precise drawing she “designs” her thoughts. She is walking through many fields of imaginations with confidence – from complicated space compositions up to a single figure. Pictorial “one-acts” take turns with richly built scenes.

Despite technical simplicity, the Čorejová’s artworks do not act as themes (or cores) of large, complicated, and not very common stories. In their motives, we can track down elements of various problematic moments present in today´s society. She is examining the issues related to the clashes of ideologies, the presence of religious or gender stereotypes, elements of absurdity of our social order. Large space of her artwork is devoted to the issue of personal freedom and internal life of an individual. To all these topics, the author is creating her own system of symbols and the viewers are gradually getting acquainted with it – they are learning the language of the author while they are “reading” her artwork.

The author is constantly returning to certain topics. She is working with Christian symbolism in the form of sacral architecture, spaces, objects, and their variations. Altars split by a perfect cut or aisles in temples overgrown by flying balloons (e.g. in The Moment of Truth) do not necessarily cause the feeling of heresy – in Maria’s tidy way of presentation, they are rather visualized images, opinions, and frustrations of a “naïve” humanist of today. She expresses her point of view on religious dogmas, limiting rules of a society or church idols (e.g. in Your Truths Are Like My Moods, etc.). She presents similar attitude also to other topics of Western civilization and its historical relicts in society, aesthetic of weapons and war (Beauty) but also for example to sport or hunting and their impact on society (for example in Little Pleasures of the Previous Days, Better Place for Life). She constantly returns to an ancient conflict of what freedom means for a man (desire to fly, to move freely, or to think) with where the limits of a man are – limits meaning also a person´s own intimate space, internal mental space or home (The Place of Ghosts). She reaches the most lyrical form in her graphical cycles focused on the motif of a boat which is sinking – or on the other hand – emerging from water. She varies this motif in many – but very similar – ways (cycles Ark and The Only Possible Solution). Often she (not only in case of these works) chooses the installation which is emphasizing the repetitiveness of these motifs. In such a case the whole unit of her pictures creates some kind of a narrative network in which the level to which is an object flooded by a black mass (water) holds the meaning of a micro-story.For the author, the presence of a dominant black space is not only an impressive artistic element which is bringing her drawing closer to a painting; often it is the main holder of the core idea of the artwork. “Black mass” is dynamically growing through the picture, it is flooding the spaces of architectural buildings, it fills an empty space, it interrupts the integrity of objects, and through its secret darkness it communicates with the action of a present figure. In such a way it creates one of the most interesting moments of the author’s artwork. It is so because this black mass is not only a holder of a negative charge of the scene in the drawing but on the contrary, it asks us to what extent is our perception influenced by prejudices and dual division of the world to “up and down”, “black and white”, “good and bad”. It looks like she is testing where we would end if we change them, if we turn them over, or if we deny their existence.

Diana Majdáková

curator

After (or rather alongside) older works which used media such as painting, video, or installation, today, drawing is the core outcome of Mária Čorejová’s thinking. The drawing sometimes – especially in the cooperation with other artists (for example with Alena Adamíková, Martin Bu, Sylvia Jokelová, Matěj Smetana, and Miriam Šebianová) became the source material for objects, animations, or painting. However, the source material this cooperation was based on was prevailingly finished, autonomous, and independent artwork which did not function only as a sketch or a draft but as a finished and masterful artwork with clear and recognizable autograph.

Today, Čorejová’s drawing is characterized by reduced black-and-white colors, work with contrast (not only between black and white but also between lines and surface or between full and empty space), placement of heterogeneous elements into one image or specific iconography, and the set of used motifs with a strong culturally (sometimes even archetypally) conditioned symbols (boat, cross, temple, house, wall/barrier/border, tent, airplane/balloon/airship, athlete, wild animals, bird, etc.).

Probably the most typical motif Mária Čorejová is using in her drawings is the black colour – visually functioning as a fluid substance or a surface which is erasing/creating an identity of space, things or figures; it flows out of/fills them in from within or selectively absorbs/uncovers their fragments. Selected ink drawing technique somehow absolutely naturally belongs to the nature of this motif and its form. The characteristics of the ink (as a material) are analogical with the fluid, dark, and clearly unidentifiable mass (as a symbol) present in the picture.

Generally we can also say that the author is moving from subjective, individual, and intimate topics towards thinking about general, public, universal, and even existential. A reflection and criticism of various cultural and social phenomena –religion and church not excluding – is represented in a major part of Čorejová’s artwork and her view is often (sometimes more and sometimes less hidden) ironic. Moreover, she is openly expressing her personal view or involvement not only through images but also through the names of her artwork (e.g. Your Truths Are Like My Moods, 2012/2014 or Where Your Arguments End, My Freedom Begins, 2012/2014).

Often she also destabilizes conventional meanings or understanding of things (and what they as signs represent) through the violation of their visual integrity, through giving them inappropriate attributes or through their presentation in strange, sometimes even surreal forms, relationships, and situations.

In the texts on the author’s artwork one can often read about scenic or latent potential for stories in her drawings. Anticipated storyline is based on images of stopped/hinted/expected movement (often of flight, heave or fall) of figures, things or disintegration of objects, architecture or fluid flow of a substance. Felt and implicit flow of visually frozen time is based on possible, anticipated or presumed situations which potentially precede or happen after the current static image. Expected action is usually minimal and artistically it is built very modestly but precisely. To use the terms based on literature – I would compare the drawings of Mária Čorejová rather to the reading of lyrical snapshots than to stories as they are not based on linear development of the storyline, but on a very modest and connotative symbolic, metaphorical or metonymic image which is present only in this moment (eo instanto). However, this moment is endless as it can be seen in three videos of Matěj Smetana (Cvičení podle Marie/Exercise According Maria, 2012 – presented at the exhibition Rozhovory, ktoré vedú inam / Conversations leading elsewhere, Kunsthalle, Bratislava, Slovakia, curators: 13 kubikov, 2013 – 2014 ) which were based on author’s drawings. In one of these Smetana’s animations, there is a boat half-full of black fluid rocking on the water while we are not sure whether it is moving somewhere or it is anchored to one point. It won’t sink; the fluid won’t either absorb it or disappear. The image is happening, it takes place in time and at the same time it is trapped in no time without any beginning or end – it is trapped in a neverending moment.

Some ambivalence, dualism, boundaries, indefiniteness, or divergence is present in Mária’s artwork not only in the relationship with the time phenomenon but is also a typical symptom of the way this author is creating her and consequently also our perception and interpretation of space, relationships among images and their meanings, and at the end also of the meaning of the artwork that comes through – metaphorically said – as an interconnection or the conjunction of several different views. Looking for example at the artwork called Milióny príbehov/Millions of Stories (2014), at the first sight we have a feeling we are looking at a church covered by snow. However, the snow is changing the tower of the building that is reminding us of a Christian temple (but similarly to other drawings – also here the characteristic cross on the top of it is missing) to a Islamic minaret or (using very secular or even “sinful” way of thinking) to phallus erected towards the sky, displayed to the world. Suddenly we are not so sure what we are looking at and what is the real meaning of the used motif. We can similarly look at the white points on the black background (stars, snowflakes, etc.) or purely black surfaces (darkness, endless space, sky, nothingness, etc.) around or inside architecture the sacral character of which we can only estimate or – according to conventions – automatically accept. Speak nothing of wide and diverging number of references and associations which can be differently interpreted by us as they are related to visual elements (e.g. space, church, minaret, phallus) and their relationships (such as space – church, church – phallus, phallus – minaret). Our perception is influenced also by the verbal information or the text which is participating in this game through the names of the artworks. In addition to already mentioned visual motifs, their meanings and relationships, we should take into consideration also Millions of Stories (present in religion, history, science, and individual lives of people) which – metaphorically – make the darkness in the temple more visible, shine lonely in the space or fall as a snow on architecture (construction) created by a man (a culture). The identity of architecture (a culture) is changing, disappearing, or starts to be similar with others which are considered to be different or even contradictory. Here, the meaning of the artwork is based on the network of various but simultaneously valid or relevant meanings and connotations.

Despite more complicated structure and divergence, the content of this but also other author’s artwork is critical and usually – at least implicitly without the need of a verbal formulation – comprehensible and accessible. C. G. Jung stated that dreams – similarly to people speaking foreign languages – are not hiding anything from us. We simply do not understand what they are saying. It might be the same with the drawings of Mária Čorejová. And as there is no dictionary added to her artworks, the best way how to learn their language and grammar would be to stay in an intensive contact with them. It definitely pays off.

Ľuboš Lehocký, art theoretician

Kresba – obyčajné a pôvodné gesto tvoriaceho človeka

„Lebo je to nielen kresba, ale aj obsah. K tomu je dôležité dodať, prečo robím kresby. Je to ten najzákladnejší výtvarný jazyk, spoločný všetkým maliarom. Je to miesto, kde vznikne idea. Všetko ostatné je pre mňa nadstavba. Mnohí umelci skicujú a potom to urobia v inom médiu. A tam to je, v tej skici. Tam je ten obsah, tá najčistejšia myšlienka.“

Kresba je akýsi nulový bod výtvarnej a zobrazujúcej tvorby. Má nespočetné množstvo foriem, je však vždy veľmi osobnou, intímnou a priamou cestou ku tlmočeniu idey. K tomu sa dostáva prostredníctvom voľného, imaginatívneho alebo konceptuálne rozvíjaného narábania s obrazom. Môže byť literárne, košato komponovaná, ale môže mať tendencie pomocou jedinej línie interpretovať zložitý obsah. Pobyt pred čistou plochou papiera je pre umelca ako okamih veľkého počiatku, meditácie, katarzie, ako nádych po narodení, ale i predstúpenie pred zrkadlo. Je pravdou, že v súčasnosti sa toto médium teší obrovskému záujmu. Jedným z dôvodov môže byť i určitý pocit presýtenia z dokonalo vyleštenej elektronickej a telematickej obraznosti, ktorá v človeku zabíja akúkoľvek vizuálnu predstavivosť, pretože jej jednoducho neposkytuje priestor.

Tento text začíname citáciou mladej slovenskej umelkyne Márie Čorejovej (1975), pretože kresbu vníma presne v tých intenciách, ktoré sú pre náš pohľad na toto médium zásadné a určujúce. Je to striedmosť, výstižnosť a schopnosť zaťať do živého. Hoci táto autorka často reflektuje veľmi osobné témy, práve kresba jej umožňuje posunúť vlastný subjektívny obsah ku uvažovaniu o jeho obecnej, univerzálnej a existenciálnej symbolike. Kresbou sa dá prirodzene sledovať tenká hranica medzi osobnou a verejnou mytológiou, náboženstvom či filozofiou. Po predchádzajúcich skúsenostiach s maliarskou tvorbou, grafickým dizajnom a kultúrnou prevádzkou Čorejová zakotvila v kresbe, pretože toto civilné a nepatetické médium, zbavené rušivého šumu estetizácie a podružných vizuálnych efektov, nemá tendencie klamať. Realitu uchopuje výtvarne, pretože sú to väčšinou javy, ktoré nie je možné transformovať do verbálneho vyjadrenia. Kresbou vyjadruje životné paradoxy, pričom túto obraznosť zrejme sýti práve jej skúsenosť s hravými optickými ilúziami uplatnenými v grafickom dizajne. Okrem toho autorka „praktizuje vizuálny hacking, a to v zmysle rôznych vrstiev tohto pojmu – ide o využívanie známych vecí iným spôsobom, ako aj nabúravanie sa do systémov.“ V minulosti zobrazovala predmety každodennej spotreby, skúmala banalitu, spytovala estetické pôsobenie prirodzene ne-zaujímavých a ne-výnimočných predmetov a rozohrávala tak úvahy o ich skrytej podstate, o ich hlbšom presahu do našej existencie. Svojou kresbou akoby popierala iba jeden jediný význam vecí a jeho obsahovú jednorozmernosť.

Anna Vartecká, art theoretician

In: Sýkorová, L.: Postkonceptuální přesahy v České kresbě